Creating scalable and maintainable front-end architecture

Modern front-end frameworks and libraries make it easy to create reusable UI components. This is a step in the right direction to create maintainable front-end applications. Yet, in many projects over the years I have found that making reusable components is often not enough.

09-2019

As requirements change, projects become difficult to maintain as it takes longer and longer to locate the correct file or debug something across multiple locations. While I can improve my searching skills, or become more proficient in using Visual Studio Code, most of the time I am not only one working on the front-end. Therefore, we need to improve the setup of our front-end projects by making them maintainable and scalable. This means that we can quickly apply changes to the current features, but also add new features much faster.

High-level architecture

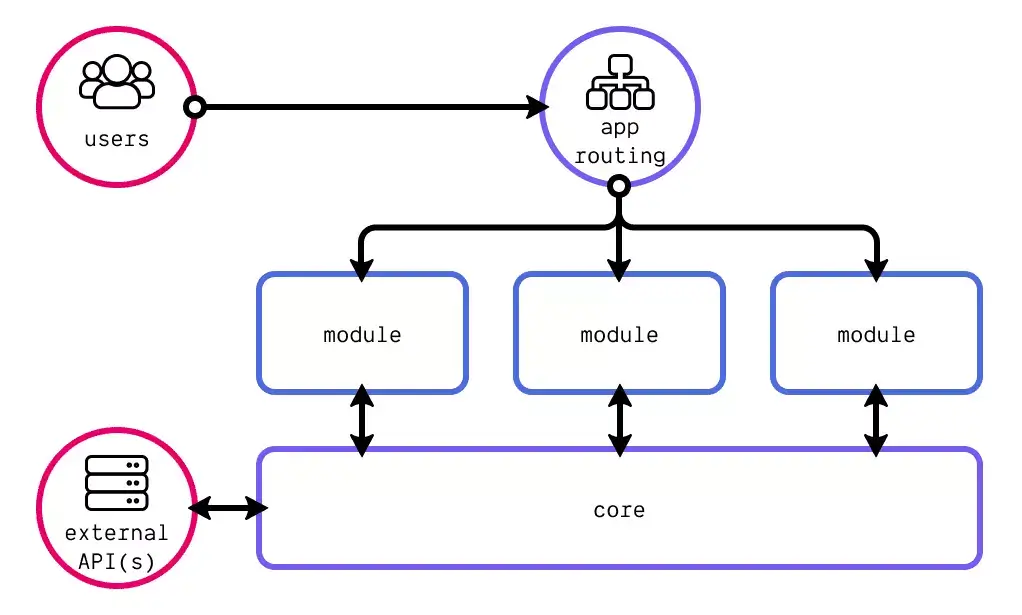

In back-end development, there are many architectural patterns we can follow. Two concepts currently used are domain-driven development (DDD) and separation of concerns (SoC). These two concepts add great value to front-end development. In DDD you take groups of similar features and decouple them as much as possible from other groups (e.g. modules). While with SoC we can separate logic, views, and data-models (e.g. using the MVC or MVVM design pattern).

Finding a scalable architecture

In traditional development, we have many architectural patterns we can follow. Two of the that are still most popular are domain-driven development (DDD) and separation of concerns (SoC). In front-end development, they too can be of great value. With DDD you try to groups of similar features and decouple them as much as possible from other groups (e.g. modules). While with SoC we, for instance, separate logic, views, and data-models (e.g. using the MVC or MVVM design pattern).

We expect modern front-end applications to do more and more of the heavy lifting. With this added complexity, bugs are becoming more frequent. We need a reliable architecture, that is both maintainable and scalable. My goal was, and still is, to find such a front-end architecture which is framework-agnostic. The architecture should provide a developer or a team to build a scalable front-end. By adopting the architecture (e.g. remove parts), you can adapt it to small and big projects.

Filling in the details

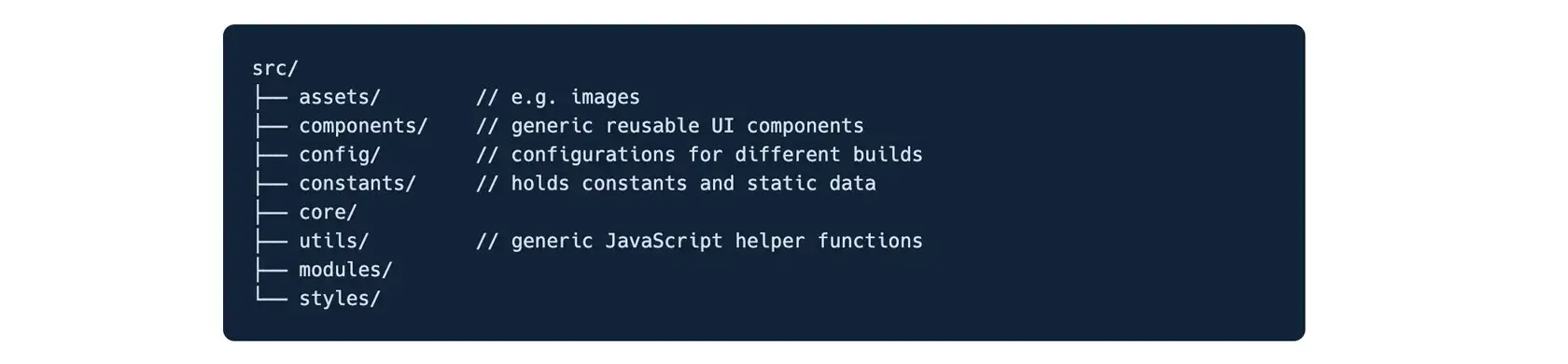

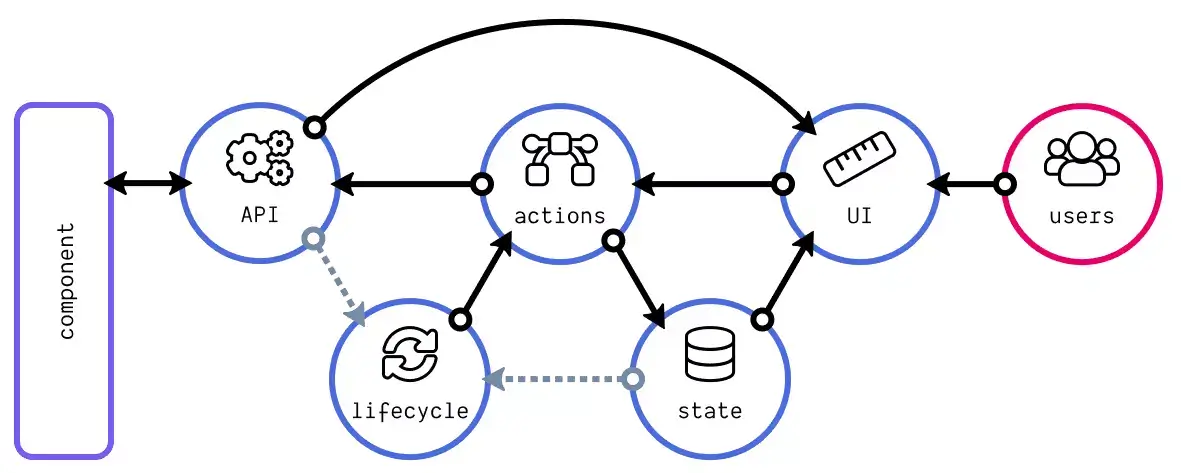

Our goal as front-end developers is to provide value to our users by letting them interact with our work. When they do, the application routing will guide the user to the correct module. Each module can is a separate domain. Business logic shapes these domains. Various modules use this logic, such as retrieving data from a back-end service. This logic is thus placed in the application layer. This is the core setup of a scalable front-end architecture. The architecture resolves around three directories. The core directory holds all code for the displayed core layer, while the modules directory holds all the different modules based on the different identified domains.

Lastly, there is the styles directory. Many prefer something like CSS-in-JS or styled-components. I prefer a solid CSS architecture, such as Harry Roberts’ ITCSS, that follows the SoC mindset of the architecture. As you can see, there are many other different directories present in the architecture. Depending on the framework or the use case, directories like hooks (for React Hooks) or mocks (for mock data during development) can be included in the project.

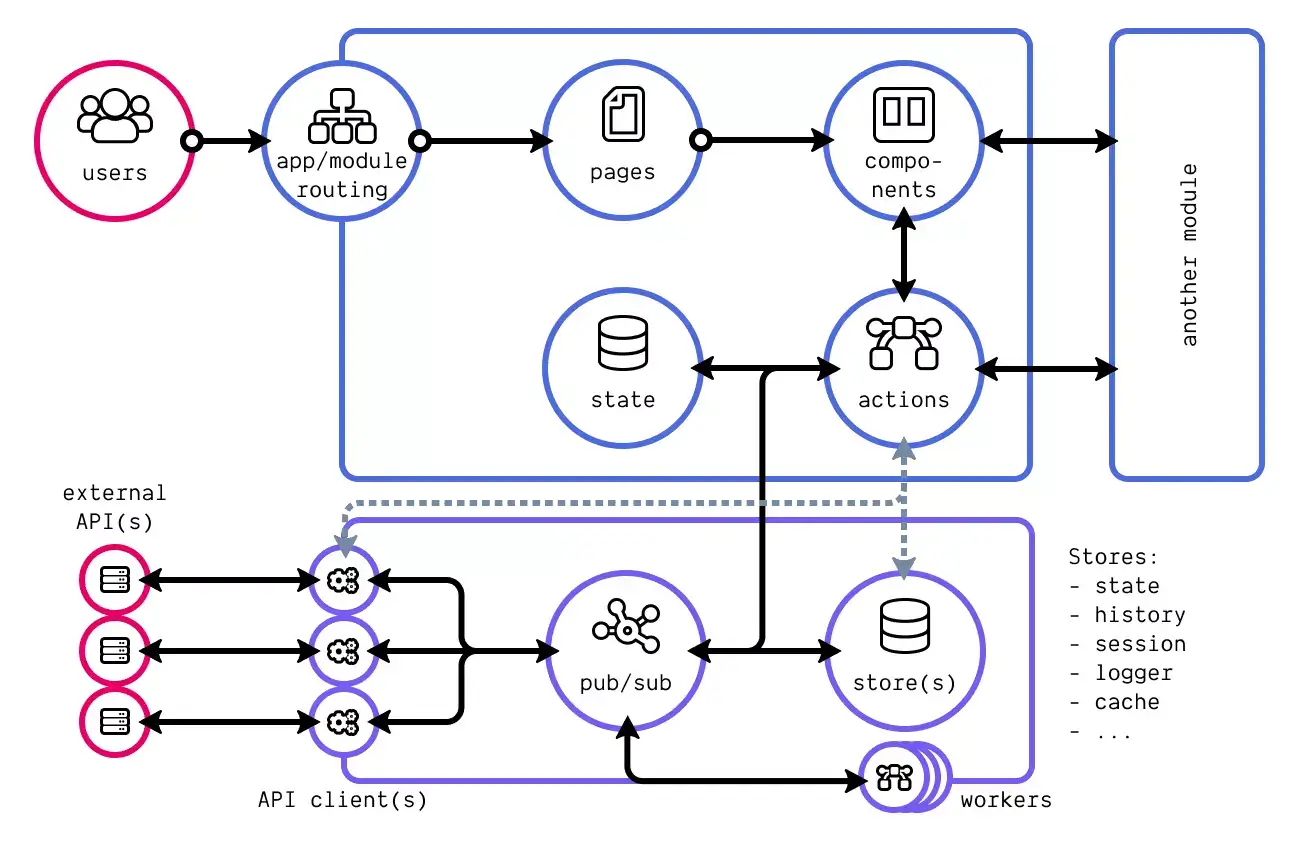

The above does not look like something special. This is a standard modular approach for development. But, by zooming in on a module and the core layer, the architecture shines. Below I zoomed in on the core layer and a single module. In the rest of this blog post, I discuss each of the different topics and the ideas behind them. The dotted connections are optional connections that you can use when you want a less complex architecture. In this case, the pub/sub and workers are removed from the architecture and actions directly talk to the stores and API clients.

The application backbone

The core layer is the backbone of the architecture. The goal of this part of the application is to be scalable and framework-agnostic. There are a few main parts in this layer: API clients, a pub/sub and one or more stores. You can include web workers for the heavy lifting on this level as well. Stores come in many sizes. At first glance, you might think about the application state. And you are right, that is one store. But what about your user’s history stack? This is, in fact, another example of a store.

When you look at stores in this light, you find many of them. Application state, navigation history, session management, API caches and logger history. These should live on an application level. This also means that they should be configured here. You can, for instance, download the history package on npm and use this for navigation history. In the store, you can expand the package by adding your functions (e.g. a different push). You can now also expose these to the rest of your application.

On the other side, we have one or more API clients. Some of our projects have a dedicated back-end service to talk to. Be it an API gateway on top of a Kubernetes cluster with many micro-services, or a single monolith back-end. But sometimes we need to connect to different external services. Each of these services requires configuration (e.g. authentication). All these configurations and invoked clients live in the core layer. This way they can be used by all modules.

A pub/sub can be used with many different goals in mind. It can loosely couple your modules from various API clients for instance. This ensures one uniform way to use API calls across your application, regardless of the API clients you are using. But, the pub/sub can have different purposes as well. When your application has an ‘auto sign out’ feature based on inactivity, the pub/sub can easily be used to reset the timer on different actions. Or you can use it to synchronous concurrent API calls at the moment you need to refresh your authentication first. And when you use a package like Pubbel as your pub/sub, you can use it to synchronise events across browser window tabs without persisting data in your localStorage.

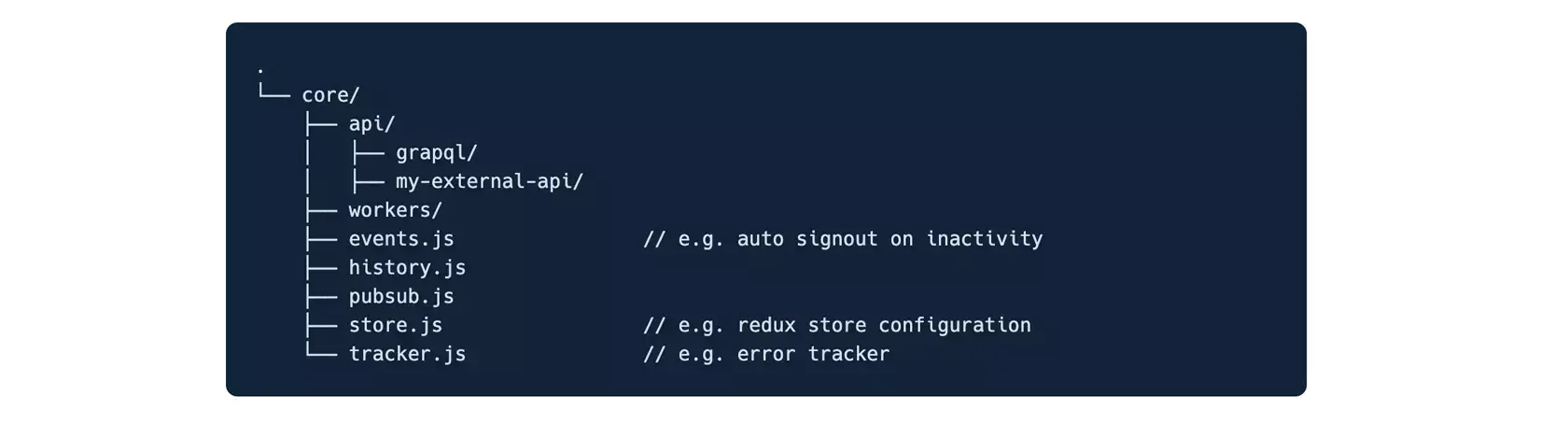

A corresponding project structure for the core directory can be something like displayed below. This is an example from one of my recent projects, although it did not include a (redux) store, as it used the cache from the GraphQL API client.

Most directories within the core folder should be self-explanatory by now. The stores directory holds all different types of persistent information for the application (e.g. session or system tracker). The events directory holds all scheduled events (e.g. an auto sign out event). The displayed PubSub is invoked and exposed in the index.js file of the core directory.

Modules, modules & more modules

What defines a module and how is it separate from complex UI components? The key-word here is business-logic. Take everything around uploading a file. You could combine generic components like a drag-and-drop zone. But, the actual uploading is different for each application, guided by technological choices. By combining the UI component and the actual action to upload a file, we create a small contained module. The moment we combine components with business logic, we convert them into modules.

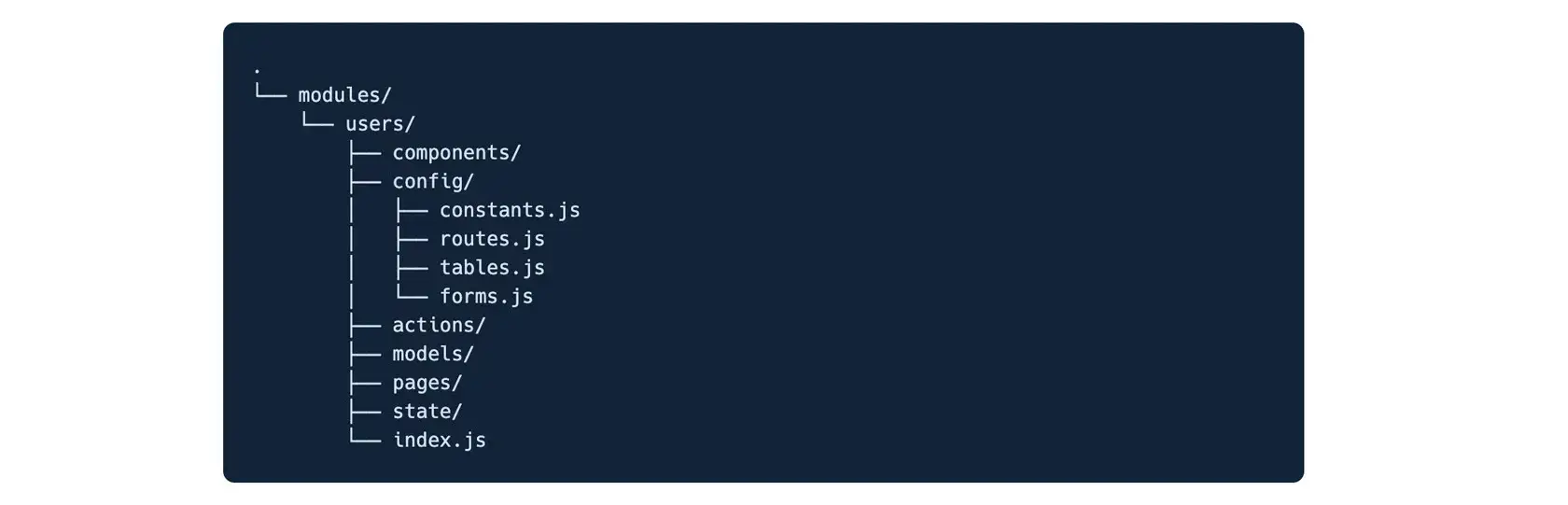

The detailed architecture diagram already shows the internals of a module. The structure of a module is inspired by the ideas of MVC and MVVM. This is reflected in the models, actions and pages/components directories.

Most times, the application routing points towards a specific module. The routing of the module itself determines which page it loads, i.e. a single page is linked to a single route. A page is what a user sees and comprises out of UI components and actions.

Actions combine ways to get capture interaction and get information out of our module or application state. Our users trigger actions when they interact with our applications. Often they are separated from UI components. But they can also live in your component. It all depends on the complexity of the problem you try to solve.

Like the core layer, a module can have its own state management and static definitions, i.e. constants. In that case, we put that code in the state (e.g. a reducer function), config and models directories. Depending on our API clients, we can add additional directories. For instance, when working with GraphQL it might be benificial to include a queries and/or mutations directory. However, as they are used inside actions most of the times, you can also include them there.

Sharing between modules

Never have I seen an application in which we could decouple modules completely. It is inevitable that you have to share models, actions and components between modules. But how can modules interact with each other?

The index.js file of a module describes which components, actions, and models are accessible for other components. So we could use a file drop-zone or the upload controller from the files module. But, sometimes we have to choose what we are exposing to other modules. Will it be an action, or are we combine the action into a component?

Let’s look at the example of a user drop-down. We can create an action that provides us all the users we can select from different modules. But, we now need to create a specific drop-down in all other modules. This might not need much effort to have a generic drop-down component. But this component might not work in a form. It might be worth the investment to create one UserDropdown component that we can use. When something changes around users, we now change only one component. So sometimes we need to choose what to expose: actions or components.

UI component architecture

One last detail level is missing still, and that is the architecture of a UI component. In a different blog post I describe this article. When you look at this anatomy, you will see some concepts back that we apply on a bigger scale. More details can be found in this article.

Conclusion

In front-end development, we often adjust our project to the framework we use. Although we live inside an ecosystem when we do so, it often is not scalable towards the future. By looking at existing concepts we can adjust our view on front-end problems. By seeing front-end concepts for what they are, we can create a scalable architecture that works for small or big, many or few.